COVID Crisis Exposes Educational Inequities Between Haves and Have Nots

The Newark Public School District announced Monday it’s dropping plans to reopen in-person classes and instead opting for a virtual year until November. The decision by the state’s largest school district comes less than a week after Governor Phil Murphy suddenly changed course, allowing public schools to go all-remote if they couldn’t meet COVID-19 health and safety guidelines for in-person teaching.

If the process appears somewhat disorganized, it may say something about the circus-like political atmosphere around the front office and its sensitive relationship with labor and other key stakeholders in the educational firmament – but it also fundamentally underscores a deep divide in New Jersey, persistent from one administration to the next, as poor children struggle amid unfair and unequal conditions now exacerbated by COVID-19.

The Governor had initially asked the state’s 600 public school districts to offer some form of in-person learning, even as the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA), the state’s largest teacher’s union and one of Murphy’s biggest supporters, called for all-remote learning statewide.

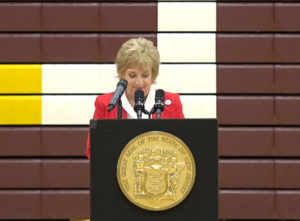

NJEA President Marie Blistan told InsiderNJ a lot of school districts were having a hard time meeting

the required guidelines to keep staff, educators and students safe.

“We’re hearing from districts that can’t even get the PPE, like the masks,” Blistan said. “What we’re advising our members to do now, and along with the principals and superintendents, is to look at the checklist that the DOE (Department of Education) has provided and it’s clear you need to attest to those health and safety standards.

“We are prepared to support our members in their actions regarding the districts,” Blistan added. “What we do know is that our members have asked that they have a seat at the table within that community and with the administration and with the school board.”

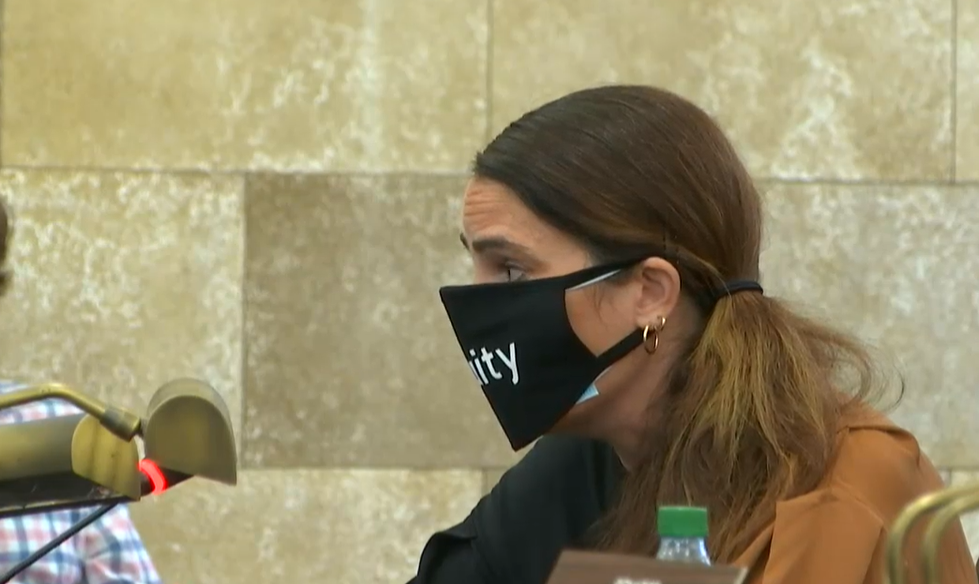

New Jersey State Senator Teresa Ruiz (D-29) says the Governor’s changes have caused confusion, especially in underserved school districts struggling with remote learning since schools shut down in March because of Covid-19 and went virtual. She says a uniform blueprint early on for all districts could have given low-income communities more time to solve technical problems like the lack of access to laptops and the internet.

“Why make superintendents and school boards and districts go running around in circles as opposed to just saying if you want to use the month of October to go virtual and work out kinks and have mock trial, school-based settings and schedule in-person special ed and do some innovative things that month — why not just allow it?” said Ruiz, a former Pre-K teacher. “Why create another confused guideline in the middle of what has to be the most turbulent public discussion for personnel, district superintendents and parents.”

Here’s why time is of the essence in low-income communities. While New Jersey consistently ranks as one of the wealthiest states in the nation with its public schools getting high marks for churning out college-ready students, all hasn’t been equal in the Garden State when it comes to education.

Over the years, a series of court decisions have tried to correct funding gaps between rich and poor school districts. But the Coronavirus Pandemic has amplified the educational inequities between the “haves” and the “have nots.”

“What the pandemic has done has forced all levels of government and policy makers to have a reckoning with issues that have faced our communities for a very, very long time,” said Ruiz, a first generation Puerto Rican-American. “Since I joined the Legislature, I have always argued about ‘learning loss,’ I have argued on the lack of resources, I have fought to move an agenda that is more equitable for students of color. Now, what the Pandemic has done is that everyone from one corner of a district to another has been talking about this ‘learning slide.’ The thing is for our Black and Brown communities, it gets even more projected and more critical, and much larger in that gap because of lack of resources and technology.”

New Jersey’s Department of Education estimates 230,000 students in New Jersey have been impacted by the “Digital Divide,” a term used to describe the gap between those who have access to technology like laptops, computers and other devices, and those who don’t.

“I’ve been screaming from the mountain top about the ‘Digital Divide’ since the second week of the pandemic when schools closed,” Ruiz said. “In some cases, they’re listening, but I think they’re listening a little too late.”

New Jersey Department of Education spokesperson Michael Yaple says the state surveyed districts in March, April and in June to see which communities needed money for technology.

In the middle of July, Murphy unveiled an initiative that directed $54 million to schools to help them close the “Digital Divide.” Ten million of that money came from a portion of the CARES Act called the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Fund (ESSER fund), and another $44 million was made available through the state’s Coronavirus Relief Fund. The administration also tapped into philanthropic support from companies and organizations. In addition, Yaple says $310 million went directly to school districts to use on whatever they needed, including technology.

But Ruiz, a Democrat like Murphy, says $54 million isn’t enough to close that technical gap and that more money needs to be allocated to low-income families to help them find creative educational solutions. For instance, some affluent parents are starting their own little schools called “Learning Pods.” Families are hiring tutors for those pods or rotating their kids at different homes. Either way, it frees up working parents and gives their children a chance to get some in-person learning in a safe environment.

Senator Ruiz says low-income families should have the same options.

“How about giving money to districts to have libraries, the Ys, and the Boys and Girls Club, Community Centers, to open them up — we should be hiring top college students, who are in education programs, and perhaps giving them credits to certification so that we can set up learning pods for families that don’t have that. The instructors are not going to be teaching them but it will be the instructor from their schools. But that person (college student) will be the adult in the room monitoring the child in the absence of a family member.”

On August 12th, New Jersey Interim Education Commissioner Kevin Dehmer said the vast majority of school reopening plans are hybrid, a combination of in-person and remote learning.

But many Urban districts like Jersey City and Bayonne notified the Department of Education they would be going all-remote. The state’s third largest city, Paterson, has had to delay its at-home school opening because more than 10,000 students had not received devices in time for the start of the school year.

“Instead of scrambling between now and some arbitrary date in September to open for in-person, we should be spending the time right now to hone those skills because at some point or another when we open for in-person, we’re going to be virtual anyway and we are demanding that we have the time,” NJEA’s Blistan said.

Republican State Assemblyman Jon Bramnick (R-21) agrees parents and children in low-income

communities need help but says he doesn’t think there’s enough money in the CARES Act. He says Murphy will have to make unpopular cuts in order to stabilize or reduce property taxes.

“Governor Murphy has almost made these decisions alone, isolated with his people,” Bramnick said. “Very rarely is he interested in reaching out to the Republican leadership.”

“Instead of holding press conferences everyday,” Bramnick added, “He should have hearings and have all kinds of citizens speak on these topics so people can listen to all different things.”

A spokesperson for Murphy says the Governor’s clearly spelled out his COVID-19 school re-opening plan and regularly holds phone briefings on important issues with legislators.

Ruiz says at some point during the school year, students need well-being and academic checks to see how they’re progressing. Ruiz calls it a “diagnostic tool,” part of a plan she’s detailed in her bill being voted on Thursday in the Senate Education Committee.

New Jersey Education Association Vice-President Sean Spiller says educators are committed to making sure no student is left behind.

“We realize that we need to be vocal about resources, support other pieces for those equity issues,” Spiller said. “Those inequities haven’t gone away because of the Coronavirus. They have only been highlighted because of the Coronavirus.”

Leave a Reply