New Jersey’s Other Famous Wilson – the One from Camden

Henry Braid Wilson was born on Mount Vernon Street in Camden, New Jersey, on February 23, 1861, just two months before South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter and the American Civil War began. From these origins, when the United States was on the verge of self-destruction, he would grow up to become one of the most prominent naval figures in modern American history. His parents were notables in town: his father, for whom he was named, serving as a city teacher, post-master, member of the Board of Education, and in other roles. Indeed, the senior Wilson’s memory lives on today. At the turn of the 20th Century, the Henry B. Wilson Family School in Camden was named for the future admiral’s father.

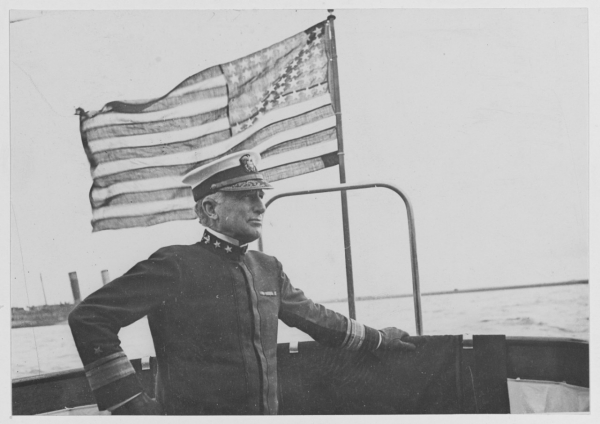

The younger Wilson graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1881 and served for over four decades. He served with bravery and distinction during the 1898 Spanish-American War and later in the Asiatic Station as executive officer of the captured Spanish vessel, Don Juan de Austria, taken during the war. In the years just prior to the First World War, Wilson served in a number of positions, eventually moving up as the Board of Inspection and Survey President. Europe had been at war for two years already when he took command of the USS Pennsylvania, a newly commissioned “super dreadnaught” battleship commissioned in June of 1916. Wilson did not serve as her captain long, however. Wilson was off to European waters, placed in command of US naval forces in that theater.

His former ship, the Pennsylvania, stayed close to home during the war, conducting training missions, but later transported the American president with whom the admiral shared a surname to the conference table for negotiations after the war’s end.

The False Armistice

While overseeing the vast logistical operations of supplying American forces and defending convoys, Wilson played a part in an incident which prematurely reported the end of the Great War. While in his office in Brest, France, Wilson received a message on November 7, 1918, that an armistice had actually been signed at 11:00 in the morning and that a ceasefire would go into effect at 2:00. This, however, was untrue, and a misunderstanding of initial German political discussions with their Allied counterparts that had just begun.

Wilson may have had good reason to believe the information to be correct at first. Bulgaria, allied with Germany, had agreed to an armistice at the end of September. The Ottoman Empire had signed an armistice with the Allies on October 30. Austria-Hungary, Germany’s closest and strongest ally, had been crushed at the foot of the Carnic Alps at Vittorio-Veneto, leading to their surrender to Italy with an armistice going into effect on November 4. This left an exhausted but still combatant Germany without an ally in the world.

Wilson passed along the message of the armistice to the president and editor of the New York World-Telegram and Sun, Roy W. Howard. The misinformation had already been spreading locally and when the news reached Washington DC, New York, and Canada about the same time, the cat was out of the bag. Celebrations broke out across the Allied nations, mistakenly hailing the end of hostilities while trench warfare actually continued across the Western Front. The war would not actually end until November 11. The town of Albion, Michigan, which had hurriedly struck up the band and paraded their town at the news, was embarrassed for sure. According to newspaper accounts this little city later said that it had been a “dress rehearsal” for the real thing to come.

Wilson Hailed A Hometown Hero

The Camden sailor, however, took responsibility for the incident but seemed to have suffered no lasting repercussions for his role in the matter and, indeed, had even loftier positions ahead of him. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and honors from Allies such as Japan, Italy, and Portugal.

According to the Chicago Tribune, “Wilson attracted attention in October, 1919, by refusing the cross of the Legion of Honor offered him by President Poincare of France. He said his work at Brest, which at that time consisted of directing American efforts to drive German submarines from the French coast, could not be regarded as duty under battle conditions and cited a navy regulation forbidding the acceptance of decorations except for acts of war. He was finally persuaded by the navy secretary to accept the honor.”

According to the History of Camden County in the Great War 1917-1918, Wilson was hailed for having “commanded a fleet that piloted more than one million soldiers to France and that fleet never lost the life of an American soldier, despite the frightfulness of the submarine warfare conducted by the enemy. During the war the fleet commanded by the Camden admiral moved all the munitions and supplies used by the American Army in France.” The account further stated that, “Besides this wonderful work his destroyers kept a constant vigilance on the seas, sinking enemy submarines. The admiral’s headquarters were at Brest, France, and by means of radio sounders the enemy wireless on their submarines were intercepted at night and the movement of their ships ascertained with the result that destroyers went in search of them and sunk many of them.”

With the end of the war, Wilson returned to his hometown of Camden on April 17, 1919, to a hero’s welcome, with a local outpouring of patriotic love and affection that would’ve rivaled the triumphal parades of Julius Caesar.

The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote a glowing account of the occasion of the Camden Victory Jubilee, where Wilson was the star. “Admiral Henry Wilson, commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Fleet,” the Inquirer read, “came to his boyhood home to be the principal guest of the city and chief reviewing officer of the jubilee. With him were national statesmen and municipal officers.” A bronze statue of a doughboy served as a cenotaph, commemorating the 135 men from Camden county who lost their lives in the war. “It mattered not whether the men were officers of enlisted men, black or white, neat or untidy, they were all soldiers and they had done all that was asked of them. Their home town honored them. The men in blue and the women in blue, too, received a welcome not one whit less feeling than their brothers in khaki. They had a certain advantage over the doughboys, for they put half a dozen of the prettiest and smartest [Navy] yeomanettes that ever wore Uncle Sam’s uniform at the had of their division. The crowd simply had to be with them.”

Admiral Wilson took the review from an enormous parade, saluting at his review stand and joined by US Senator David Baird, Congressman William J. Browning, and Camden City Clerk W.D. Brown. Afterwards, the dignitaries joined a victory banquet at the armory which had been four days in the making, thanks to Red Cross workers. Mayor Ellis said of Wilson in a speech, “This is one of the happiest moments of my life. I have waited patiently through moments of trial for the glad day when I could bid you welcome to the City of Camden once again. We are planning to erect a lasting memorial in memory of those heroes who gave their lives and in memory of the valiant deeds you performed on land and sea. Camden will always cherish the memory of this day, revere the memory of your dead comrades and will inscribe your valiant deeds on that memorial. I bid you welcome in the name of the most patriotic little city in America. I thank you.”

Prosecutor Charles Wolverton said that, “It was a Camden officer, in the person of Admiral Wilson, who taught the Kaiser and his war-lords that there is no such word as ‘impossible’ to be found in all the historic records of the American Navy.”

Post-War Career

From July of 1919 until June of 1921, Admiral Wilson served as Commander-in-Chief, US Atlantic Fleet. Between 1921-1925 he held the post of Commander-in-Chief of the US Battle Fleet, touring the Caribbean and Pacific, and Superintendent of the US Naval Academy.

While at the Naval Academy, Wilson wanted to make the institution “more humane” and cracked down on hazing among the midshipmen. He also established the academy’s first PT department and the Ring Dance. The Ring Dance, a formal ball, is considered a “rite-of-passage” where midshipmen have their class rings blessed by navy chaplains in a bowl of water, “collected from the seven seas”. The tradition represents their marriage to the Navy.

In honor of the hometown hero, a two-and-a-half mile length of US Route 30, between the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Camden to the Pennsauken Route 70 overpass, was changed from Bridge Approach Boulevard to Admiral Wilson Boulevard in 1929. The name was in effect, but not official until Camden Mayor Winfield Price oversaw the passage of a resolution in 1937, solidifying the name in legality, according to the Courier-Post. Neighboring Pennsauken Township followed suit.

The Camden native retired and, in 1954, he died in New York City, just three weeks shy of his 93rd birthday. He was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery, where his wife, Ada Chapman Wilson, was later interred when she died in the summer of 1963, also at the age of 92.

In addition to the naming of Admiral Wilson Boulevard, Camden’s seafaring son was honored when the USS Henry B. Wilson (DDG-7) was commissioned in 1960. A destroyer armed with guided missiles, the USS Henry B. Wilson conducted tests throughout the Pacific, later serving in support of the Vietnam War. The vessel earned the Republic of Vietnam’s Meritorious Unit Citation and operated in subsequent evacuation missions in 1975. The ship bearing the admiral’s name was decommissioned in 1989.

Leave a Reply