The Thorny Question of Race at the Heart of NJ Redistricting

You generally can’t go wrong quoting Martin Luther King Jr.

And Barbara Eames of Morris County did just that the other day when speaking to the state’s Apportionment Commission. She referenced King’s famous quote about judging people by the content of their character and not the color of their skin.

Then she got to her main point.

Eames said the ongoing redistricting process seemingly has been “all about ethnicity, nationality and race.”

That it has.

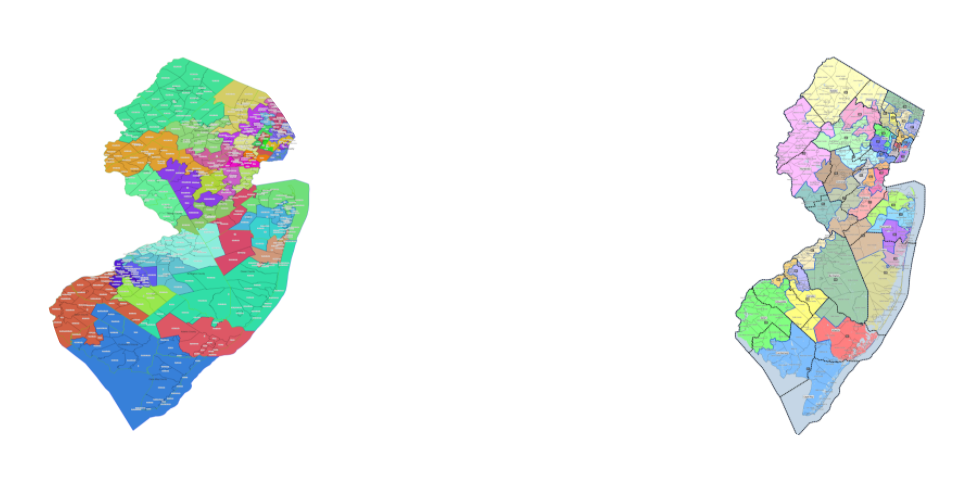

The panel remapping the state’s 40 Legislative districts, which plans to deliberate on a final map this week, has held 11 public hearings.

And yes, there has been much talk from the public about creating districts that reflect New Jersey’s growing diversity. Speakers at the hearings mentioned a need for districts that just about guaranteed representation from a variety of ethnic groups, among them Blacks, Latinos, South Asians, Muslims and Arabs.

A self-proclaimed “unity map” proposed by a coalition of mostly liberal groups proposed 20 “majority-minority” districts. That would be half the districts in the state. By comparison, the maps proposed by Democrats and Republicans would have 17 such districts, according to the coalition.

Recognizing changing demographics is something everyone in public life must take seriously.

Yet, the fixation on “ethnicity, nationality and race” raises questions that some may not want to address.

Do voters simply want to elect candidates from their own ethnic group or race, or do they want candidates who support their views?

From a national perspective, Blacks are a minority in the U.S., but many whites voted – twice – for Barack Obama. Likewise in New Jersey, many whites have voted for our two senators – Bob Menendez and Cory Booker – both of whom are minorities.

Even in legislative races, some minority candidates don’t seem to need a minority district to win.

Look at LD-1 in south Jersey, which has a Black population of about 11 percent, according to the 2020 Census. One of the Assembly members there is Antwan McClellan, a Black Republican.

At the other end of the state in Bergen County is LD-37, which has a Black population of about 14 percent. The state senator there is Gordon Johnson, an African-American.

In Central Jersey’s LD-11, Democratic state Sen. Vin Gopal is an Indian-America in a district where the Indian population is about 5 percent.

These may be exceptions, but maybe not.

Could it be that voters are more sophisticated about this than the activists? In other words, perhaps voters don’t care that much about race if they think a candidate is in line with their views.

The redistricting battle will end soon – likely by the end of the month. A map will be solidified and politicians will live with it for the next 10 years.

But the emphasis on race and ethnicity needs to be critically examined.

One of the messages of King and the 1960’s civil rights movement was to see people as people despite racial and ethnic differences.

On that score, why can’t an Asian-American legislator represent people in his, or her, district regardless of their race? Likewise, is not a white lawmaker capable of representing Black and Hispanic people living in his district?

Racial equality means – or should mean – that all people have the same basic desire for good schools, safe communities, good health care, a clean environment and a safety net for those who need it.

How to achieve that is what politicians should debate, not how best to separate – or dare we say, segregate – voters along racial and ethnic lines.

Leave a Reply