Comparing the Crises: Christie and Sandy and Murphy and COVID, and the Coming Election

Chris Christie and Phil Murphy are two governors who are, in many ways, very different. But they are also governors who have faced extraordinary external, devastating threats. Each man has, in his time and in his way, dealt with it. For Chris Christie, this was Hurricane Sandy which pulverized the Garden State in 2012. For Phil Murphy, his dragon was and continues to be the COVID-19 pandemic.

These two crises would be some of the defining aspects of both of their administrations. In the case of Chris Christie, his leadership in the aftermath of Sandy propelled him to meteoric highs in the polls, enjoying the widespread support of the New Jersey population. His gruff, tough, no-nonsense style which had been called bullying and demeaning before (and again after) seemed like the kind of approach New Jersey needed. The boardwalk was destroyed, homes were without power for days, the Star Jet roller coaster in Seaside Heights had been swept into the sea and became a powerful image to remind mankind of the strength of nature. Quite simply, New Jerseyans didn’t need a nice guy trying to coax everyone along, they wanted a strong leader who could deliver results. And on the whole, Christie was successful.

Had Christie’s political career concluded there, he would have been remembered as one of the greats to occupy the governor’s chair, regardless of any and all misgivings from the insiders with respect to Christie’s time as US Attorney. However, Christie filed for re-election and handily snuffed out Barbara Buono’s challenge, gaining another term. It was in this second term that Christie went from one of the most popular governors to one of the least in New Jersey history. The mighty waves that battered the New Jersey coast had carried Christie up with them, and with their recession back into the sea, so Christie descended as well. But this was due to hubris. Bridgegate. Chris Christie on a beach chair became and remains an extraordinarily popular meme. His poor showing during his run for the presidency in the 2016 presidential primary showed how far he had slipped in a short time. That he had lost it—indeed, his presidential campaigning while still governor of New Jersey had hurt him even more at home, where he became regarded as an absent governor. After taking just over 7% in the New Hampshire primary, Christie withdrew from the race. At home, Lt. Governor Kim Guadagno’s campaign to succeed her boss would be badly anchored by her association with Christie. Phil Murphy–a Democrat, product of Goldman Sachs not unlike Governor Jon Corzine and former ambassador to Germany–would sweep the polls and take office in 2018.

Phil Murphy’s term had been characterized by a contentious relationship with Senate President Steve Sweeney, clashing with special interests in the state on the right for being too far left and on the left for not being left enough, the Katie Brennan case—and then the coronavirus struck the Garden State in the winter of 2020.

Like Hurricane Sandy, the coronavirus came from beyond New Jersey’s borders but struck the state hard and fast. Both Sandy and the coronavirus were seen well in advance. Destruction being wrought on Caribbean islands, infections rising exponentially in China and east Asia, Iran, and Italy. In the case of Sandy, the government made meaningful preparations in advance. Christie ordered the evacuation of the state’s barrier islands, the closure of the casinos—and in a remarkable act of charity, the suspension of northbound tolls. Train services, anticipating the worst, called off their services. Utility companies prepared for long days ahead. Halloween was right around the corner, but the monster that was Hurricane Sandy was all-too-real and bringing with it widespread devastation. In terms of size, Sandy was enormous and wheeled left, smashing into New Jersey and tearing apart all before it with the irresistible power of nature. Once the storm had dissipated, over 2 million residents were without electricity, some people would be in the dark for several days while utility workers labored around the clock to restore critical services. The CDC reported 34 New Jerseyans died directly because of Sandy—four from drowning—and the hurricane caused an estimated $30 billion in economic loss. Governor Christie swung into action. Frequent press conferences, tours of the devastated Jersey Shore, and a tireless effort to bring order back to the chaos made Christie, politically, untouchable.

ELECTION YEARS

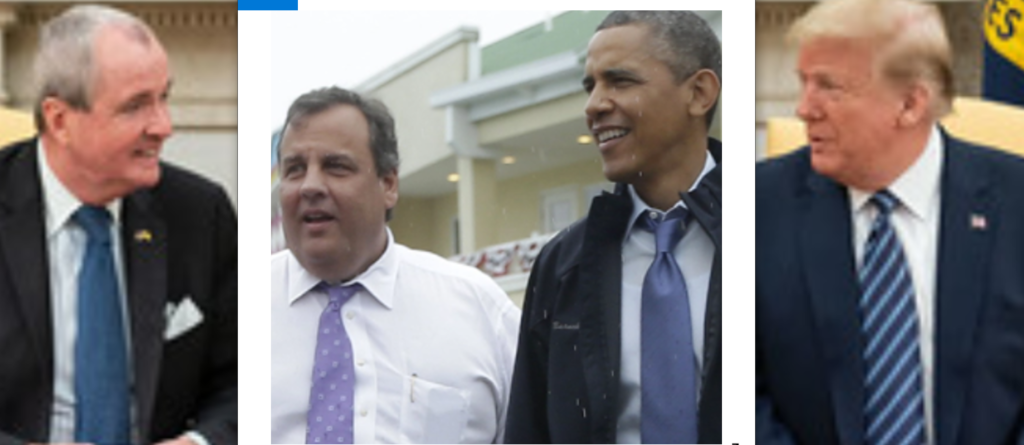

Sandy struck during a presidential election year with a gubernatorial election year following, as did COVID-19. In both cases the governor and president were of opposite parties, but in need of a close working relationship for the good of the public. Christie had been campaigning for Mitt Romney but asked for President Obama to come to New Jersey and toured the damage with him. Christie told MSNBC that Obama had given him a direct phone number and said not to hesitate to call him. Christie’s warm reception of the president was criticized by some conservatives but the governor, rightly, had put his state above politics and needed to have a strong, frank relationship between the president and the governor to aid in the recovery efforts. Just over a week after Sandy, it was election day. Although Christie was riding high, New Jersey overwhelming voted in favor of President Obama over Mitt Romney, whom the governor had championed. According to FDU polls, prior to Sandy, Christie had a 56% approval rating that jumped to 77% after the hurricane struck. In the summer of 2017, after his abortive attempt to run for president and after being shunned by President Donald Trump, Christie had, according to Quinnipiac, a 15% approval rating, the lowest in state history.

In 2020, Phil Murphy had to fight a different kind of battle and in this case, the federal government had no plan in place to effectively deal with the coronavirus. Indeed, while Christie was back in private life, the White House via John Bolton had “streamlined” the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense, leaving the country less prepared to respond to COVID-19.

Murphy, like many other governors, was left without guidance and without assistance from the federal government. Entities like the Center for Disease Control and U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases were often in conflict with the president and at times with each other. Phil Murphy, nevertheless, managed to obtain significant funding and resources from President Trump with whom he apparently had a friendly relationship, despite being ideologically his anthesis. On April 30, 2020, Murphy met with Trump on obtaining resources to battle the pandemic. Murphy turned on the charm and was able to obtain much-needed ventilators and PPE which was then in short supply. Their meeting was downright chummy and all partisan issues were put aside. The president said of New Jersey, “It’s a great place and a great state. They have a wonderful man that’s running it, he runs it with heart and with brains. He’s done a terrific job… He’s one of the governors who has really done the job. He stepped up to the plate and swung.” Murphy, in turn, was complimentary. “We couldn’t be making the progress without you and your administration. To you and to your incredibly talented team, with a very heavy dose of New Jersey blood in your team… thank you for everything… Thank you for your partnership and leadership.”

“It’s a beautiful state,” Trump said, “people don’t understand New Jersey quite, it’s a beautiful state and it’s great to have you as the governor–as a Democrat, I’ll get myself in trouble, but that’s OK, I have to tell the truth, he’s something.”

Murphy had been endorsed in 2017 by Vice President Biden, who called the election “the single most important” race. In 2020, Murphy had also supported Joe Biden, but only in May. Murphy, conscious of his need to maintain a relationship with a White House that was based more on personality than on policy, was not as vociferous a critic of Trump as he had been before the pandemic. There were glaring exceptions, of course. “The notion of using tear gas or smoke devices or rubber bullets on peaceful protesters in exchange for a photo-op is disgraceful,” Murphy said after protestors in Lafayette Park were violently swept aside and President Trump took a picture holding a Bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church Parish House. Nevertheless, Murphy’s endorsement of Joe Biden was hardly unexpected.

SCALE AND PUBLIC RESPONSE

Generally speaking, a leader’s popularity tends to rise during a time of disaster or emergency if it stems from an external source, whether a hurricane like Sandy or a terrorist attack like 9/11 or a military attack like Pearl Harbor. In the case of the latter, American reluctance to enter the Second World War was shaken off and FDR led the country to war, carried on by his successor, Harry Truman. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush enjoyed record high approval as the nation looked for leadership from the Oval Office. The same was true of Sandy.

There was a clear, identifiable threat. Sandy was a storm which appeared, caused destruction, and then disappeared. The public endured hardship together—not wholly equally, of course—but nevertheless, New Jerseyans stood together and, as the popular slogan at the time read, were “Stronger than the Storm.” The public was also called upon to do relatively little other than wait. When Governor Christie was asked by a reporter when PSEG would have power restored, he answered in his usually frank style, “How the hell should I know?” And he was honest—no one could predict the future. But he was accessible and he was visible. As a leader, he checked all the boxes and eventually things got better.

With the case of COVID-19, there was also an external threat but there the differences become more apparent. This was an invisible enemy and there was no physical destruction wrought. There were no smoking ships sinking into burning, oil-slicked waters in the harbor. There were no twisted carnival rides dragged out into the surf. Instead, people were getting sick. A long incubation period, coupled with uncertainty surrounding the specifics of a novel virus—literally, a new disease that was a variant of the deadly but short-lived SARS virus from 2003—meant that people were not as informed as to what to do. How was the public to prepare? The governor enacted a state of emergency and began shutdowns. A stay-at-home order was issued. Schools were closed and had to switch to a new frontier: virtual learning. The history is so recent it need not be elaborated on further here, but unlike Sandy, the public was unable to escape the fact that they were going to be factors in the fight. Murphy needed public cooperation and public action to support medical services and dramatically alter their own behavior for the benefit of themselves but also for others, be they family, friends, or strangers. Further compounding the problem? The public as well as the government lacked practical experience as well as resources (initially) to deal with the threat. The US had not experienced a pandemic of this nature since the Spanish Flu a century prior.

If the enemy is visible, the dynamic changes entirely. Sandy could not be defeated, but she could be overcome. The coronavirus is another matter entirely.

Unlike Christie, Murphy did not have the benefit of overseeing a public-private cooperative effort for recovery “after the fact”. Government action could not and would not overcome the virus alone as it was not only spreading within the state, but also coming in from those outside New Jersey’s borders. People had to sacrifice, albeit differently than their parents and grandparents did in the 1940s. The state reported the first official coronavirus death in the state on March 10, 2020. By June 13, more New Jerseyans had died from the invisible enemy than in the Second World War. At the time of this writing, shortly after Murphy upbraided anti-mask, anti-vax protestors as “the ultimate knuckleheads,” the state reported the deaths of 23,887.

Chris Christie had the benefit of a “brief” disaster. Murphy, however, must contend with a crisis entering its 18th month. Nothing is better for a leader’s prestige than a short, decisive victory. Like Cincinnatus, the Roman consul-turned-dictator-turned-private-citizen, it is also a way to end a political career and enjoy a glittering legacy in private life. But unlike Cincinnatus, few leaders choose to or even want to voluntarily bow out on a high note. Stepping away from power is not inherent in those who exercise it, leaving those who do in the highest esteem—our first president, for example. Nevertheless, Christie had every right to expect a successful second term and his easy victory seemed to reinforce that notion. Murphy still is likely to win in November and potentially break state tradition in that no Democratic governor has been reelected since 1977.

Christie’s administration has plenty of baggage, he left office in the inverse position of his post-Sandy status. Murphy finds himself in an almost-Churchillian position, facing a long campaign requiring the public to trust and comply with state recommendations. And unlike Churchill, Murphy does not enjoy the complete confidence of the public. Distrust in governmental institutions is at an all time high, coupled with vaccine hesitancy and large segments of the population unwilling to comply with masking protocols. New Jersey is faring better than many other states as far as vaccination goes, perhaps owing to generally wide access to free vaccines and having one of the most educated populations in the country. But at the end of the day, Murphy can only ask people to do the right thing. The most effective weapon against the virus is a population with a high vaccination rate combined with common sense practices.

THE ENDGAME

The English author George Orwell had said, “Pacifism is objectively pro-fascist. This is elementary common sense. If you hamper the war effort of one side, you automatically help out that of the other. Nor is there any real way of remaining outside such a war as the present one. In practice, ‘he that is not with me is against me’.”

If Murphy was to view the coronavirus as a war, then he was already at a disadvantage. The battlefields are everywhere, the soldiers are the frontline workers, hospital staff, care givers, and individual residents taking precautions, getting vaccinated, and consciously altering their pre-2020 behavior in conventionally abnormal but necessary ways. This is a lot to ask of the public, especially for prolonged periods of time. The “pacifists” in Orwell’s phrasing as they relate to 2021 are the people Murphy described as “knuckleheads”—the ones not part of the war effort, sacrifice, and undertaking with no concrete finish line to strive for.

Christie did not have to deal with this. No one walking outside of a padded cell with small windows could be called a hurricane denier or maintain that the floods were a governmental scheme for controlling the population. Christie also enjoyed support from the top, headed by his political—but not personal—rival, President Obama.

With Murphy still fighting his battle with the coronavirus, he faces Jack Ciattarelli in the November general election. For hard-nosed political reality, the coronavirus has defined Murphy’s administration thus far, and continues to. Christie and Sandy are solidly in the books, open to examination, investigation, and interpretation. The coronavirus has yet to see its ink dry on the pages and only time will tell how this chapter in New Jersey’s story is written.

Apparently, there are no sources for metrics or best practices for assessing the emergency management role of a governor, including the development and implementation of disaster mitigation plans, actions to take during and

immediately after the disaster unfolds, and coordination of long-term recovery

activities. file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/dot_34038_DS1.pdf

There are only optics.

“When Governor Christie was asked by a reporter when PSEG would have power restored, he answered in his usually frank style, “How the hell should I know?” And he was honest—no one could predict the future. But he was accessible and he was visible.”

The Governor’s response was not an indicator of competent leadership for those expecting that he could simply reach out — directly or through staff members — to Ralph Izzo, chairman of the board, president, and CEO of PSEG to obtain his best current estimate on when power would be restored based on the extent of power loss and the availability of repair crews.