The Inestimable Shape of Gaetano Bresci’s Heinous Act

As August 23 is the 93rd anniversary of the execution of Italian-American anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, InsiderNJ looks to one of New Jersey’s most high-profile anarchists and the effects of his actions on world history.

Paterson was a hotbed of anarchists at the turn of the century and this essay will elaborate on its connection with one particular figure who stands above all others in the Italian anarchist ranks for the most high-profile murder of his time: Gaetano Bresci.

Anarchism in the 19th Century and early 20th Century was the stuff of terrorism and fear, like the subsequent Red Scare and more current fear of Islamist terrorism. Anarchism was, in a familiar sense, an international movement but without international coordination. While conferences and congresses had been held in various European and American cities, the anarchist element had both a philosophical as well as operational wing.

The period in question was a time of rapid change and industrialization. Cities were being linked by railroads, steam ships were carrying cargo across the oceans faster than ever, and factory chimneys reached higher and higher, belching black smoke into the skies. Pastoral lands were being gridded up by streets and developed. Brick and mortar was the hallmark sign of progress, and the more of it, the better. But with the production of so many new material goods and the rising standard of living for some came grinding poverty and a sense of hopelessness for others. The urban poor were the object of Charles Dickens’ work, himself a product of the workhouse, while genteel society preferred to look the other way and concentrate on innovation and gilding the cages they had built around themselves.

Anarchism, at its core, asserts that human liberty is at odds with the societal constructs of coercion. From there, any myriad flavor of anarchism follows. Anarcho-communism, anarcho-socialism, anarcho-libertarianism, anarcho-syndicalism, all influenced by various thinkers and cultures. The bottom line, however, is that the status quo had to go. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau had penned in “The Social Contract” in 1762, “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains. One thinks himself the master of others, and still remains a greater slave than they.”

But first, some context is necessary.

In Europe, revolutions swept through the continent in 1848. Violent demonstrations for national determination and the rights of the individual at the expense of autocracy were largely suppressed by force. But the revolutionary fervor did not vanish. Felice Orsini, an Italian revolutionary, had attempted to kill Emperor Louis Napoleon in 1858, seeing him as the chief impediment to Italian independence. The attempt was unsuccessful. Injured by his own bomb, Orsini was arrested and executed by guillotine. Among anarchist and revolutionary circles, Orsini became a martyr.

Across the forests and steppes, Tsar Alexander II, the most liberal of the Romanovs, was a target for revolutionaries. After surviving assassination attempts from a radical peasant, a Polish nationalist, a revolutionary student, and a carpenter-turned-bomber, Alexander “the Liberator” was finally killed by a team of assassins who slaughtered the tsar with a bomb thrown at his carriage on March 13, 1881. The killing of the autocrat inspired anarchists with a concept known as “propaganda by deed” where a dramatic example was hoped to inspire others. The bloody assassination also hardened the hearts of his heirs, Tsars Alexander III and Nicholas II against liberalization, and (ultimately fatally) strengthened Russia’s authoritarianism.

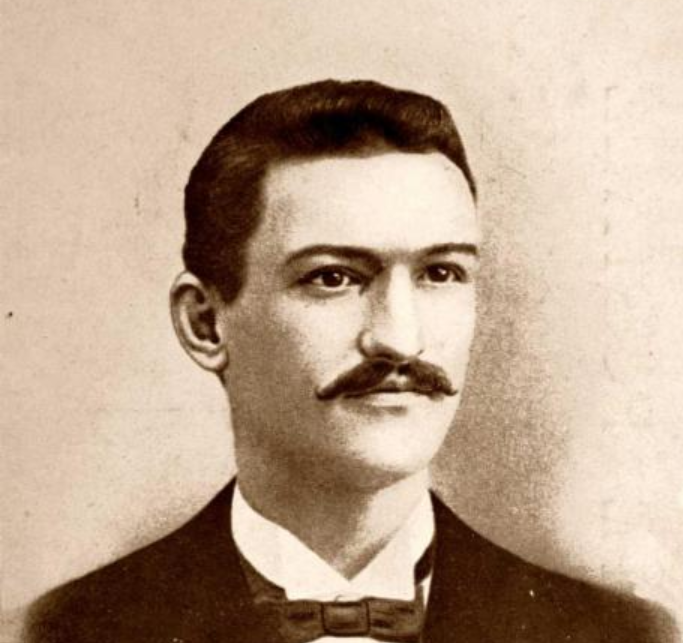

Gaetano Bresci was born in Tuscany in 1869. At this time, Italy had only been united as one country under the Savoia royal family for 8 years. According to a 1900 copy of the New York Times, he emigrated as a young man to Paterson, New Jersey, and had lived there for six years. He worked in the silk mills as a weaver, like so many other Patersonians.

However, Bresci was neither destitute nor looking to leave Italy behind forever. The anarchist community in Paterson had a number of Italians in their ranks and was known worldwide as a stronghold for anarchist sympathizers. It should come as little surprise, given that Paterson was an industrial city undergoing rapid change and development.

Bresci became active in anarchist circles and even helped establish an anarchist newspaper in Paterson, La Questione Sociale (The Social Question).

In Italy, the second Savoia king on the throne was Umberto I. Umberto had not received the same degree of education and instruction on the workings of state due to a frosty relationship with his revered father and founder of the kingdom, Vittorio Emanuele II. As such, Umberto was known for a bellicose disposition, hardened by his experience on the battlefield like his father, but not tempered with his father’s wisdom. As Italy’s industrialization continued, prosperity did not follow equitably. Despite being a constitutional monarchy, the king also had a habit of interfering and influencing government inappropriately. He sought to expand Italian colonies in Africa while illiteracy and hunger remained widespread throughout the congested industrial north and impoverished agrarian south.

In 1898, a bad harvest had led to a wheat shortage and rising prices. Additionally, American imports were affected by the Spanish-American War. Imports were also subject to tariffs. In May, a revolt broke out in southern Italy, demanding “bread and work” among the working class. The revolts quickly spread, suppressed in the major southern cities, but taking a particularly violent turn in the north. Police attempts to control the demonstrations fueled the fires when protestors were shot and killed, infuriating the demonstrators further as thousands took to the streets. In the major Lombard city of Milan, some 60,000 protestors took the city and General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris was called in with thousands of troops, comprised of infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

On May 7, 1898, the Times reported, “The rioters [in Pavia] stretched chains across the streets in order to prevent cavalry charges. Several soldiers and civilians were injured. A riotous mob surrounded a detachment of troops at Sesto Fiorintino, and the soldiers fired a volley, killing three of their assailants and wounding four others. There were fresh disorders at Prato, ten miles northwest of Florence, to-day. The extension of the bread riots to Central and Northern Italy is regarded as an extremely serious feature of the case, because the people in that section are more enlightened and better educated, and there would therefore be difficulty in suppressing agitation.”

It is said that when you have only a hammer for a tool, all your problems look like nails. Beccaris proved himself willing and able to drop that hammer in suppressing the revolt. In front of the great cathedral, the Duomo, barricades were erected and manned by troops. Soldiers fired onto demonstrators and cannon were used, striking a monastery housing the poor on the charity of the monks. The revolt came to a decisive end, with estimates of 300-400 demonstrators killed and a thousand wounded, according to the New York Times.

Approximately 1,500 people were convicted by military courts derided by journalists and attorneys as a miscarriage of justice and the judicial process. Beccaris was decorated by the king for his service.

It is believed that this incident is what finally inspired Bresci to act upon his desire to kill King Umberto.

Taking some money from the newspaper, Bresci booked himself passage back to Italy. He knew that the king would be in the Lombard city of Monza, where he had a royal villa. With a small caliber revolver, Bresci determined to avenge the king’s victims.

Umberto was a hated figure among the anarchists and had survived assassination attempts from Giovanni Passannante and Pietro Umberto Acciatrito. According to Scott Mehl, as Umberto was watching a sporting competition on July 29, 1900, the king opted not to wear a protective jacket he had adopted following past assassination attempts due to the intense heat. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

Night had set in and the king went to his carriage which was to take him to the royal villa. Some locals had gathered to see their sovereign and wave. As the king greeted the crowd, the man who was born in Italy but made in Paterson stepped forward and leveled the gun. Four shots rang out, three of them striking the king.

Umberto collapsed forward, quickly losing consciousness from the bullets which passed through his body. In the chaos which followed, the king was rushed to the villa and police quickly apprehended Bresci.

Royal physicians were unable to save the king and he died at approximately 11:30 p.m.

Bresci was charged with regicide and brought to trial, defended by Francesco Saverio Merlino, a libertarian socialist theorist who had a long history of anarchist activism himself. As Italy had abolished the death penalty, Bresci was sentenced to life imprisonment on an island in the Tyrrhenian Sea where he later died in mysterious circumstances, alleged to have hanged himself in 1901.

Bresci’s assassination of the king sent shockwaves around the world. As an advocate of propaganda by deed, like the attempts on the lives of Louis Napoleon, Alexander, and Umberto, Bresci’s actions inspired more anarchists. In the United States, which Bresci had called home, Leon Czolgosz, had believed that America was being crushed by unjust and oppressive economic conditions. With the killing of Umberto I, however, Czolgosz, himself of the anarchist persuasion, decided to emulate the action.

President William McKinley was receiving visitors at the Pan-American Exhibition in Buffalo on August 31, 1901. Czolgosz approached the president who offered his hand and shot him twice in the stomach. McKinley would die on September 14, America’s most high-profile victim of the anarchists. Theodore Roosevelt, assuming the presidency, said, that any question compared to the suppression of anarchy “sinks into insignificance.”

Had not the injustices of Umberto finally pushed the Paterson-based radical to act on assassination, it is likely McKinley would have lived out the rest of his days naturally. What influence the murder of McKinley had on President Roosevelt’s tenure, or whether Teddy may have ever become an occupant of the Oval Office, is inestimable for the shaping of America’s path through the 20th Century.

Leave a Reply