History at Hinchliffe Stadium as Eastside Ghosts Take the Field

PATERSON – People talk about the healing powers of water and, maybe to a little lesser extent, baseball.

If the city of Paterson suffered significant gashes throughout its history, these two forces – the Passaic River and the game of baseball – come together here in a way that also celebrates history, specifically of the American breed ultimately overcoming infamy.

The murderers who flew an airplane into the Twin Towers occupied a rooming house just a handful of blocks from this place, in an all-but-forgotten gloomy brick building, overshadowed, and then some, by a circus maximus of civilization otherwise known as Hinchliffe Stadium, the sports temple that nurtured ballplayer Larry Doby, which sits just above the Great Falls of Paterson.

Built in the Great Depression, opened in 1932 and condemned in 1997, Hinchliffe served as the home of two Negro League Baseball Teams before the integration of Major League Baseball, and holds the memories of 20 Hall of Fame Baseball Players, including the great Doby of Eastside High School, the first African-American ballplayer in the American League, just 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson joined the National League.

Today, just ahead of the grand reopening of Hinchliffe this Friday, the Eastside High School Ghosts charged onto the field to host Don Bosco, the first of a double header of old school Silk City baseball sponsored by Mayor Andre Sayegh.

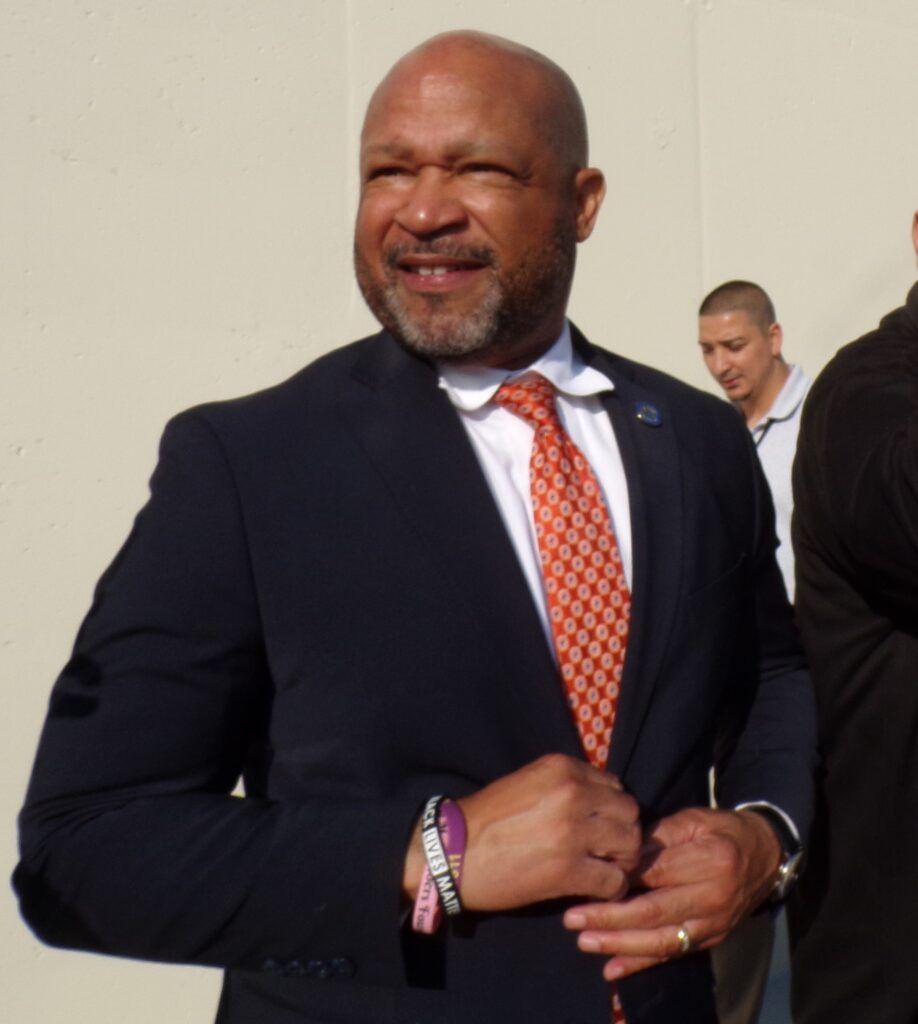

“It’s exciting,” said a grinning Assemblyman Benjie Wimberly (D-35), standing in a crowd of former ballplayers and fans, and cheering on the Ghosts, a team Wimberly coached himself for nine years.

He rushed out of the end of an Assembly Budget Meeting and raced up the Garden State Parkway to get to the game.

They threw out the first pitch before the workday ended, so the bleachers weren’t yet packed, but the Patersonians here early loved seeing the blue uniforms of their team on the bright green ballfield with Garrett Mountain in the distance.

“Beer here,” a fan mugged, finding the groove of the game and the atmosphere conducive to the evocations of prime-time baseball.

“Hot dogs,” he added.

Scattered laughs ensued.

A Don Bosco player stepped to the plate.

He looked like a young Dave Winfield.

He had a man on base.

It didn’t look good.

On the second or third pitch, Winfield drilled a deep ball that hooked foul over the first baseman’s head.

Oh, no.

“If he straightens that out” – someone murmured.

He did.

BAM!

The gap in center field awaited the fast-diving ball with open green arms.

“Coach,” yelled the pretend hot dog man. “Pobre hombre. Cambia el pitcher, coach.”

A few other Paterson fans barked him down.

“No, it’s too early,” someone snapped.

Winfield stood on second base, with a man driven in for the first score of the game.

“It’s ok,” a Paterson fan yelled down to the field from the brilliant white stucco of the stands. “They got one. We’ll get ’em back.”

Wimberly reveled in the groove.

The lawmaker and legendary football coach actually coached the last game here before the stadium closed. His father, Benjamin Wimberly, played football in Hinchliffe, and so did his uncles.

He grew up with the stadium symbolic of something great.

“The biggest thing was coming here on Thanksgiving Day – there were 10,000 people here,” the assembly recalled. “I live on the East Side. We used to walk from the East Side of town like the Cosby kids. We’d get here and get the old dirty dogs – those foot-long hotdogs. Then, going home, we’d stop and get hot pizza for 25 cents a slice.”

“The biggest thing was coming here on Thanksgiving Day – there were 10,000 people here,” the assembly recalled. “I live on the East Side. We used to walk from the East Side of town like the Cosby kids. We’d get here and get the old dirty dogs – those foot-long hotdogs. Then, going home, we’d stop and get hot pizza for 25 cents a slice.”

He said he’s looking forward to the Jackals coming to Hinchliffe, but the consummate local high school coach regarded the players on the field in front of him tonight and said, almost in awe, “These great young men.”

Another great young man, Larry Doby, got his start here, before making history as the first African American to play pro ball in the American League.

Wimberly knew Larry Doby.

“Larry connected me with [businessman and sports team owner] Joe Taub, who donated $3,000 for our uniforms,” Wimberly told InsiderNJ.

What would Larry Doby – who died in 2003 – think about the players for his alma mater, Eastside High School, taking the field today?

“He’s be so happy,” said Wimberly “He’d be here.

“And he’d be humble,” the assemblyman added. “He was always humble. Other people talked about history. He was humble.”

A Ghost slammed a ball into the same gap in the field, this time between two Don Bosco outfielders and Wimberly the coach suddenly transformed out of assemblyman interview mode and waved his arms, “Go, go, go, go!”

The Ghost stood on second thumping his chest.

“No,” yelled Wimberly. “Go to third. Go to third. GO TO THIRD!”

He had time.

But he didn’t go to third.

Groans ensued among the old ballplayers and fans.

Oh, well.

“That’s ok,” someone chirped.

Paterson was on base.

It felt like a metaphor, as deep as the river and the game itself.

Don Bosco would go on to give the local club a beating in their inaugural Hinchliffe game.

But the humility of Larry Doby came through in the testament of living history.

In a place barely clinging to the summit of the falls a few years back, the ghosts of the past infused the Ghosts of the present and of the future, all of them, by the grace of the game, the gloved conquerors of infamy.

“He rushed out of an Assembly Budget Meeting and raced up the Garden State Parkway to get to the game.”

This is why NJ legislators should denied the chance to hold a second job aling with their legislative Duties. Pay them a $100,000 a year and ban them from holding a side job.