Jon Corzine, the Club, and New Jersey’s Painful Search for its Political Self Amid the Murphy-Norcross Badlands

New Jersey could not function, or be at peace with itself, without an abiding sense of paranoia and dysfunction.

Chris Christie had understood the political culture, and capitalized on it when he occupied the office of U.S. Attorney.

There are no registered Democrats or Republicans, attorney Michael Critchley once told a roomful of insiders in Belmar.

“There are only registered opportunists,” he noted.

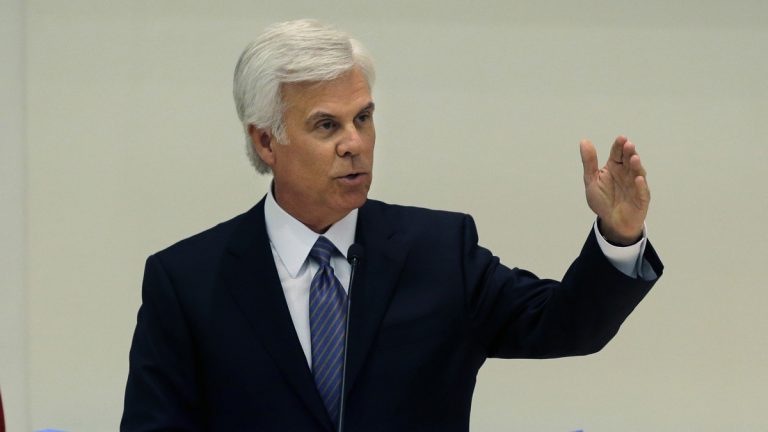

Now Critchley acts as counsel to a select legislative committee preparing its final investigative report into the hiring practices of the administration of Governor Phil Murphy. On the other side of that legal divide sits Chris Porrino, former state attorney general for Christie, who advises or advised members of the sitting administration caught in the headlights of the charges examined by the committee. And while that report on the so-called Alvarez scandal gets finalized, Critchley and Porrino both simultaneously represent the interests of South Jersey Democratic Party Power Broker George Norcross (pictured, above) as the co-signers of a letter targeting a task force formed by the governor to look into the activities of the state Economic Development Authority (EDA) during the Christie years.

Norcross is fighting back because the name of Kevin Sheehan, an attorney at Parker McCay, surfaced in the wake of a criminal referral to law enforcement authorities by the task force. Parker McCay is the law firm of Philip Norcross, brother of George.

Christie was not in the room on that occasion when Critchley spoke.

He didn’t have to be there.

Everyone who supported him, or who would ultimately come to support him, most of them Democrats, sat there, including multiple man-servants in the GN3 orbit.

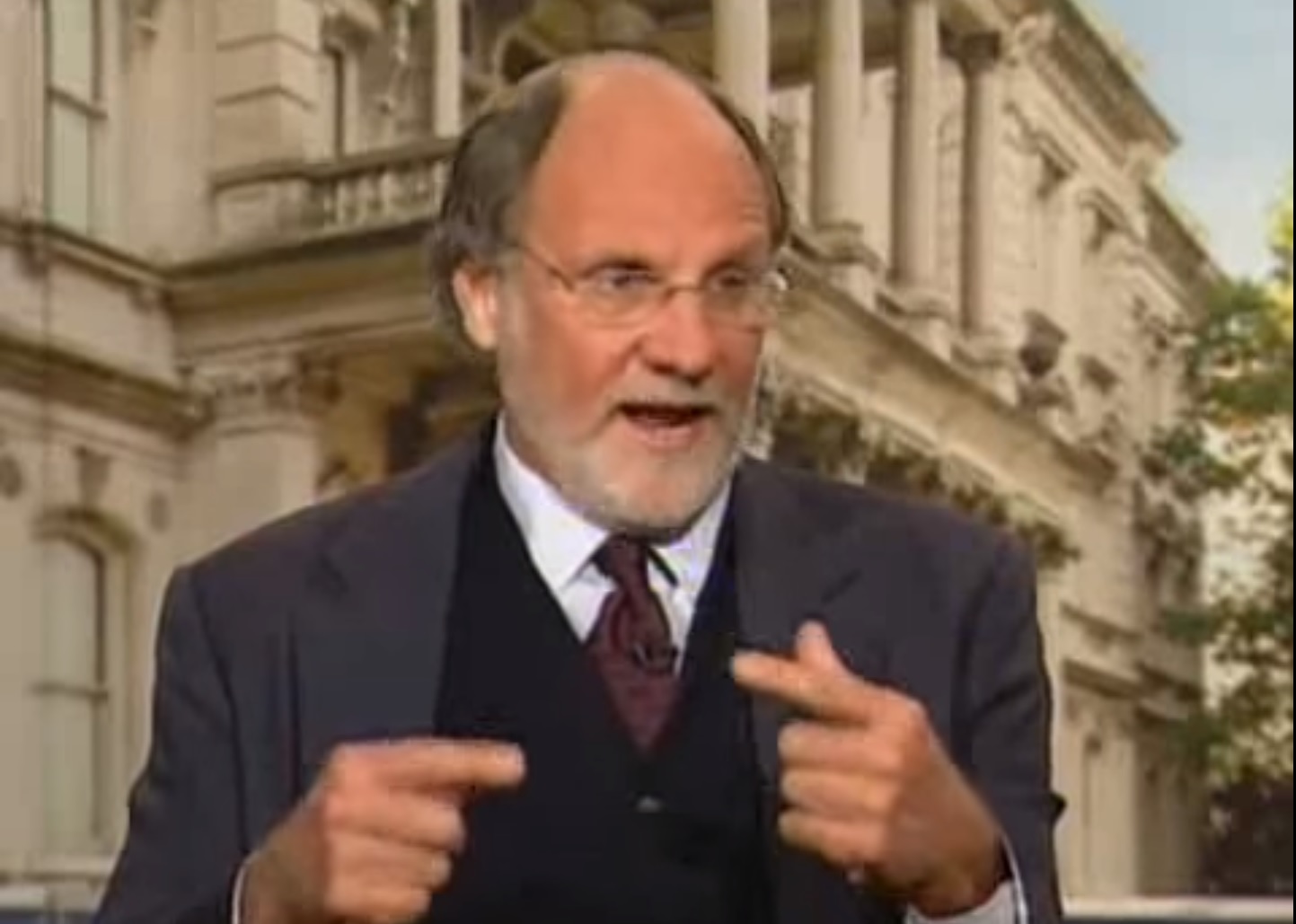

Governor Jon Corzine was there that day.

“I’m really, really sorry,” an ironworker told him.

“What?” said the governor.

“Dude, I’m really, really sorry,” the tradesman repeated.

The governor walked away with the same basically benign – almost kind – expression he had on his face at the beginning of the encounter.

When InsiderNJ later asked the ironworker what he was talking about, he said, “I just feel bad for the guy.

“He’s so out of place,” he added as the black SUV with tinted glass and government plates lurched away from the curb.

As much as he tried to be part of the club, Corzine must have been painfully aware of the disconnect between himself and New Jersey’s political class when, on another occasion, someone at Steve Adubato’s annual North Ward event slung him a sack of phony money and the sitting governor, trying to contribute to the sketch, uncomfortably tossed the sack to Christie.

Christie didn’t skip a beat.

“You didn’t want me to be the only one who didn’t take money from you,” said the Republican, and the house packed with Democrats roared.

The day after the election, the governor-elect choked back tears at Adubato’s side when he recalled growing up in Newark. “He’s Italian,” the elder Adubato told InsiderNJ, after the election, after Christie had beaten Corzine, the same way he beat him in that room at the North Ward Center.

“Murphy’s not Jon Corzine,” Murphy’s allies insisted in the lead-up to 2017.

They said it over and over and over.

And over.

Soon there were people in what was left of the media typing that very line, “Murphy’s not Corzine,” to blot out the sting of Goldman Sachs, where both Democrats worked prior to becoming governor.

Operatives around Murphy scored a victory whenever they could get cynical, craggy scribes to refer to Murphy as “ambassador” instead of “ex-Goldman Sachs guy.”

But it didn’t last.

It couldn’t.

For even without the Goldman Sachs factor, when it came to Norcross, like Corzine, Murphy was at a significant disadvantage on one critical point.

Most or many of the people in the Democratic Party had some sort of connective tissue to the South Jersey Machine.

Few had ever worked outside the auspices of government and its fissures and fixtures.

This was all they knew.

All they had.

If it wasn’t a lobbying connection, it was a party connection.

It it didn’t give the immediate appearance of an alliance, it was the memory of money in a critical campaign, or an endorsement at an opportune time.

It was a favor.

A phone call.

A job.

Murphy had no deep loyalties like that in New Jersey.

He glided over the swamp, and, his critics said, would prove to govern over it, not in it.

Never in it.

There are human beings walking around in this state wielding power, who could be presented with pictures of Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, Jr., and George Norcross, and only recognize – based on their perception of political relevance – Norcross.

They are individuals – many of them – who seem to be socially awkward or lacking who take solace in the fact that Norcross knows their name, or embodies, within the parochial framework of this existence, a kind of social grace as a consequence of wealth, that rubs off favorably in the animal hothouse of the Democratic (or Republican) Party.

And so Murphy was at a disadvantage.

Corzine even had a leg up on him.

He fed the machine, threw a lot of money around, just as Christie said he did.

“But Phil has a personality, unlike Corzine,” was the common rejoinder.

Corzine didn’t need one, at least for a time.

Even at a church rally for him just before Christie beat him, he was reaching into his wallet and handing money to the pastor.

Cash.

For his part, Murphy’s personality still resonated among public sector employees and their allies.

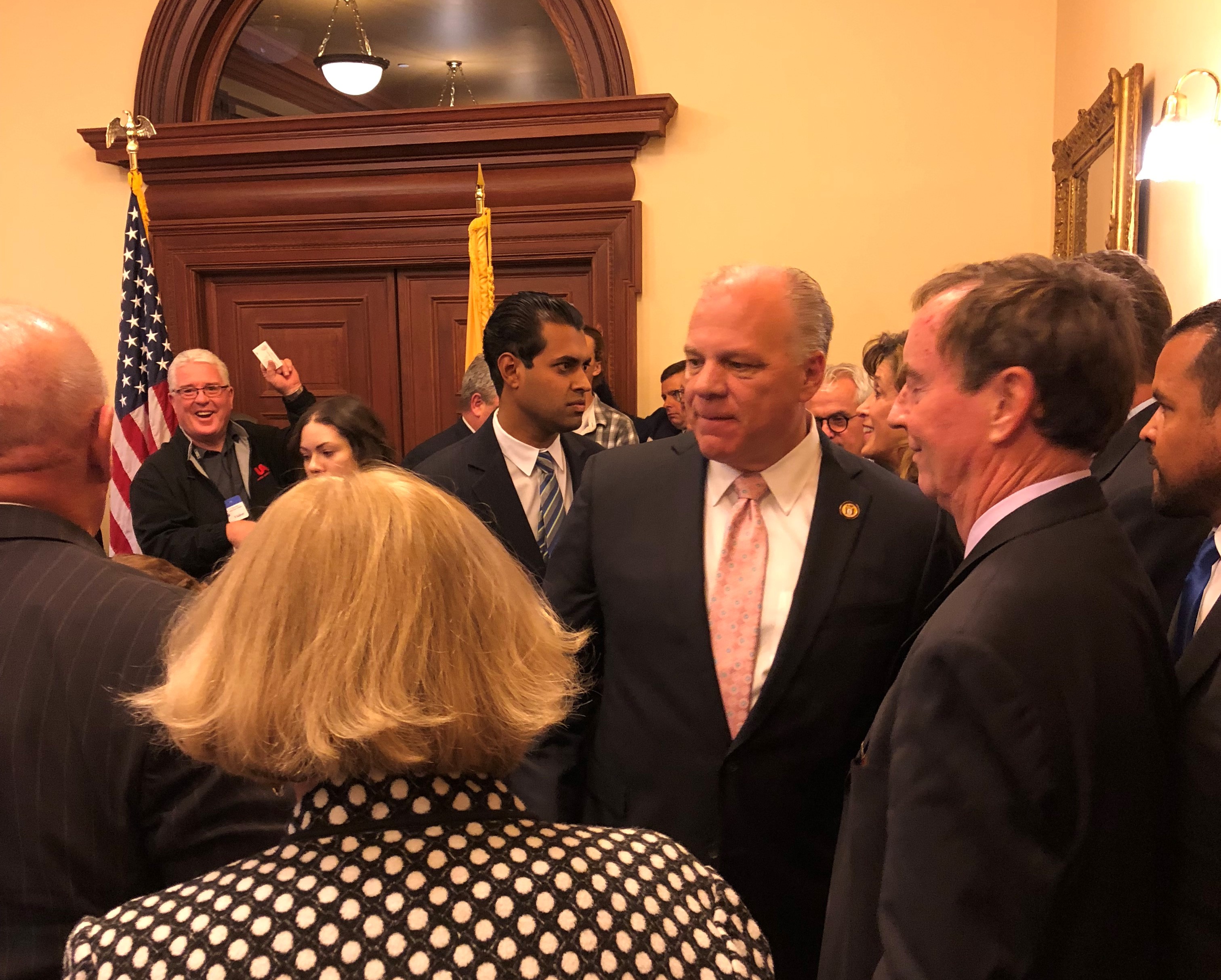

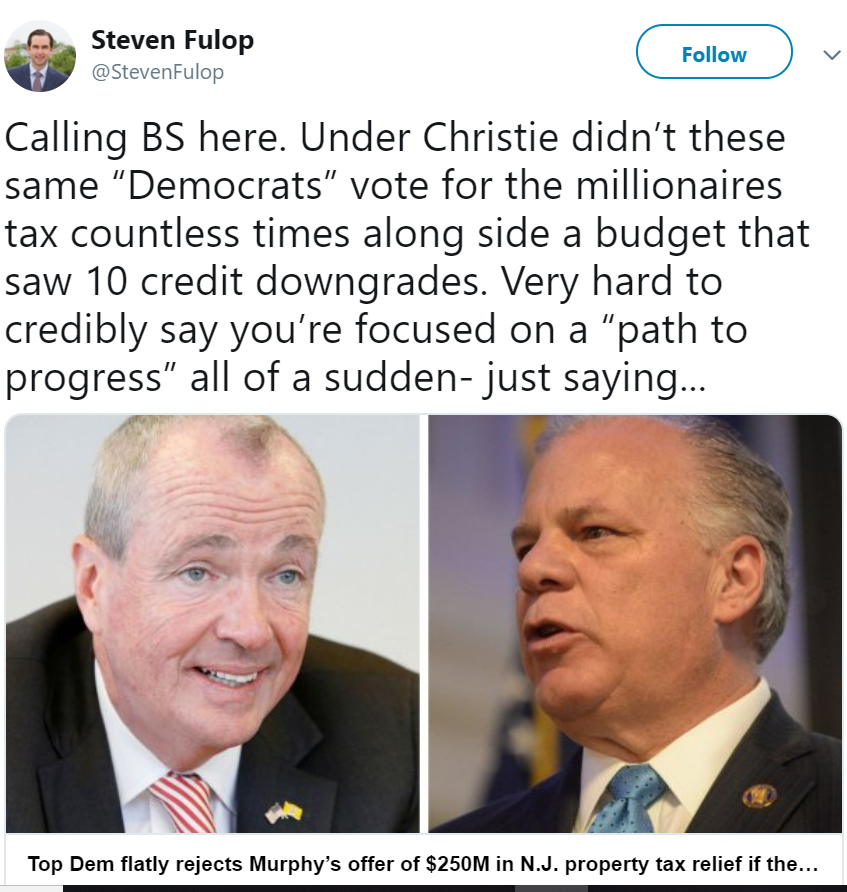

It was about policy, not personality, or so they argued at any number of Senate President Steve Sweeney’s (D-3) Path to Progress events.

But in that sphere of influence bifurcated between public sector and building trades, going back to 2007 (and before that), pre-Governor Christie, when teachers and CWA workers stood up in a ballroom at the Borgata and exhorted AFL-CIO Prez Charlie Wowkanech to punish labor brother Sweeney for trying – in his capacity as a state senator – to overhaul public pensions and benefits, Murphy met dead stares from Building Trades labor.

When one of their number tries to make nice, they disappear – or at least their job does.

Ever since the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) tried (and failed) to get rid of Sweeney in 2017, payback for partnering with Christie to increase the retirement age, freeze cost-of-living adjustments and force workers and state government to pay more, Sweeney has hit back in the halls of the statehouse.

His target?

NJEA ally Murphy.

His beef?

Governmentally unsure of himself.

Slow of foot.

His people?

Worse.

“They needed a kill-shot on Steve, and didn’t get it, so now Steve’s going to make Murphy pay,” was the assessment of ten sources.

20.

Now, every time they sit down with Sweeney and Speaker Craig Coughlin to have a conversation about

something substantive, the front office reps find themselves forced into having to admit to being the least prepared people in the room. “Where are we?” is the most obvious way they telegraph a lack of grounded facts or institutional knowledge in a room crammed with operatives who fed from the hands of Joe Doria and Joe Roberts.

Norcross’ allies had penetrated the fabric of the political world with the argument that the governor and the front office could not compete with the mechanical political know-how of the establishment, and those whispers had become their own cotton-mouthed atmosphere. “The governor wants to cut ribbons, not govern,” was the kind of comment circulating every day in the vicinity of the statehouse.

They made it about mechanics, not substance.

But mechanics is substance in politics, they argued.

It wasn’t policy per say, notwithstanding an immediate (or ongoing) differentiation between Sweeney and the governor on the millionaire’s tax.

It was know-how.

As if government were a skill Sweeney had and the governor lacked.

And it boomeranged and pin-balled because the establishment valued precisely that skill.

Anyone who hadn’t lived it that way either felt like he was watching Goodfellas, or seethed finally with discomfort.

The establishment lacked, particularly in these times.

On his way to finally condemning a political club that was so out of it, so disconnected from reality, that it could take the country to war in Vietnam, journalist David Halberstam detailed the esprit de corps, military skills learned in combat, self-discipline, patriotism and education on display in the Kennedy administration in his book The Best and the Brightest.

But this group seemed, in the main, ill-prepared to drop and kick out even 10 solid push-ups.

If it lacked social grace it was because it consumed a culture that demanded its absence.

It was profane.

It was almost ungrammatical in its insistence on cramming “f-ck” into every communique, as if demonstrable inner confusion transmitted energy.

It apparently lacked the ability to thrive in a world that didn’t contain a public dime.

It lacked the ability to read, truly read.

The absence of valued discipline in the culture beyond what the self could gorge itself on made self-mythology increasingly the only value. It wasn’t only Jersey. The transmogrification of Trump to the presidency underscored the ingested incense-power of self the magnified culture permitted, in fact demanded, along with accompanying canned laughter cronyism.

But Trump, like Murphy, only governed to his base, was governmentally inept, a show horse, and arrived to the capitol as a complete outsider, noted an insider. It was a stretch, but he stood by it.

The New Jersey political establishment instead delighted (and indulged a cult of personality) in the proximity of Trump’s friend, Norcross, the insider. If there was someone they could respect it was George, because George, like them, knew the smart play in government, but he also (unlike them) had made it in the private sector.

They weren’t like Murphy.

But George was.

In the Cayman Islands, he could see beyond the narrow and parochial world of walls they saw.

Plus, he was like them.

He cared enough to come back.

He stayed.

He was of the world they understood.

And he was more savvy and smooth than Trump, let’s face it.

He was the ultimate comic book centaur in a culture where a new generation of government bureaucrats saw themselves as characters in a comic book movie.

And Murphy wasn’t in it or of it.

So when the news hit that Murphy’s AG was under the hood and looking at the EDA tax incentives, and an “unregistered lobbyist,” and the attorneys close to Christie, who got the system and would never leave it, and Norcross, who got the system and would never leave it, had huddled up to defend them, the establishment could only talk about retribution.

Not against Christie.

Not against Norcross.

Murphy’s attorney general, Gurbir Grewal, held a supposed criminal referral submitted by the task force – conceivably a deadly legal instrument – and yet – and this was the crux of the standoff – he and Murphy did not wield Norcross’ New Jersey calling card: political influence.

But even if the worst befell the boss, even if Sheehan, the attorney whose name surfaced in connection

with the legislative process, didn’t simply assume the role of – and this was a going comparison in the days since the news – Bridget Kelly – as he hung on the question of whether his alleged manipulation of legislation that would directly favor his or his firm’s client(s) is an indictable offense, the establishment sweated with the possibility of retribution.

“It’s not a kill-shot,” a source grunted, referring to Norcross’ alleged culpability in the “unregistered lobbying” caper.

“It had better be a kill-shot,” someone else said.

That word again.

The same assessment of when the NJEA missed Sweeney.

He came on stronger.

In the cigar bars and taverns and cocktail lounges, they blandly speculated about who it might be in Murphy world who would take the hit, refusing to align with Murphy, for who could be sure he was going to stick around. They talked about what Coughlin would do, pulled north and southward, and generally concluded he would try to stay poker faced, but lean south if it turned into an all-out war, because the south wasn’t going anywhere and, again, Murphy could vanish tomorrow.

What sane person would stick around, even the most corrosive-element grounded operative asked with a half grin.

Who but only a tight circle of opportunists could test the fate of the New Jersey establishment and side with Murphy against Norcross, ran the conventional wisdom from inside the machine.

They went through the names.

It wouldn’t be former Speaker Sheila Oliver, now Murphy’s lieutenant governor, who posted the allegedly bad bill in question back in 2013, which only movement conservative Senator Mike Doherty (R-23) ultimately opposed.

She was of the system.

She had found a way to paralyze the male establishment that tried to box her in, and survive – even off the reservation, even after they discarded her and after her failed rage-against-the-machine bid for U.S. senate – she found a way – in part on the strength of Essex County connectivity – to revivify.

She would survive when Murphy was gone, they said.

Even U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) – whose political operatives played politics with South Jersey – belonged.

“I’m going to get lawyered up, just in case,” a source confessed to InsiderNJ, sitting on his stool, eyes glazed over by the ballgame.

But Murphy.

Murphy didn’t belong, they said.

Even Woodrow Wilson knew enough to get out of New Jersey once he stuck it to the party bosses.

Up and out.

“I have it on good authority that they’re already talking to Joe [Biden] and Kamala [Harris] about getting Phil into a [Democratic] cabinet,” a statehouse source swore to InsiderNJ.

The source didn’t mention Booker, who’s running for president, and who could save them the troubles of those maneuvers if he won.

It was bad.

It was the almost same space to which the club continually tried to consign Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop, who never quite completely weathered his initial 2004 challenge of then-Congressman (and now U.S. Senator) Bob Menendez, even as the latter tried to engineer him into the governor chair before Murphy beat him. The fact that Murphy outfoxed the mayor reaffirmed Menendez’s distrust.

“I will not go down this path again,” the senator raged, when Fulop dropped out of the 2017 governor’s contest and someone suggested he back Murphy.

What did he mean by again?

He didn’t want another Corzine.

Re-liberated from the barn of those libations, Fulop teed off on Twitter against old nemesis Sweeney and the establishment.

Norcross henchmen fired back.

The Democratic Primary war averted when the party pooh-bahs picked nice Goldman guy Murphy instead of North Jersey’s Fulop and South Jersey’s Sweeney seemed perfectly calibrated – with backroom daggers instead of fixed bayonets – in time for budget season.

“There’s going to be a shutdown,” a source groaned.

But it went deeper than the programmed conversations.

State Street has a lot of money invested in the status quo. The boards, the commissions, the agencies — they are largely still populated by GN3/CC allies who are the ones awarding the professional contracts, making the regulatory decisions that impact companies, possessing their own patronage hiring capabilities. Judgeships, boards of businesses, even watchdogs all connect to that tag team. Bottom line: the elected officials need the boss’ super PAC more than they need the Governor or State Committee. The lobbyists know, when push comes to shove, they must heel to the establishment while acting friendly enough to the young ones in the Front Office so the governor’s people don’t pick up on true allegiances. The narrative had been firmly established, or so they thought: just wait Murphy out. In the words of one interpreting source: “As soon as we emasculate him with the State Committee, continue to block his agenda… and relentlessly demoralize him, his wife and his team — he will be out of here , yeah, let’s say it will be with new Dem President in Washington.” All the money is tied to GN3 world and Murphy is a potential disruptor. But – and this was new territory, what really terrified “George about this Task Force is its independence.” There were no obvious tentacles, no backdoor way to get them to slow down, no way to kill it. The attacks about Jim Walden not being licensed in New Jersey seemed more a reflection of a mindset if, “hey, you’re not supposed to be working with people I don’t own.”

This, the source insisted, was foreign turf “for George.”

Still, the swamp gurgled in its own broth, boiling it down to something mobster-comprehensible.

Even if they couldn’t praise his government prowess, even if they didn’t know the name Woodrow Wilson or could identify his bronze bust at the statehouse, even the dimmest of pro-status quo government bulbs conceded that if he sticks at it, Murphy “has balls.”

“If he doesn’t blink the way he did with last year’s budget and the way he did with [former Schools Development Authority CEO] Lizette [Delgado Polanco], then I gotta say, ‘he’s got balls,'” the source admitted. “He don’t care if we don’t care.”

It was no small compliment in New Jersey politics.

Christie, after all, had worked with Norcross, not bucked him.

Maybe, a new thought occurred, Murphy really wasn’t like Corzine.

On the heels of yet another predictable round of the same South Jersey establishment types raising Cain in defense of their boss, a slow news day statement appeared.

It was from former Governor Corzine, and it read in part:

“Today, I am pleased to see Camden’s substantial progress. Hard work and focused initiatives by many stakeholders, including George Norcross, deserve credit for the results. Even so, more needs to be done. State administered economic investments and incentives within the proper legal and accountability framework should continue to play an essential role.”

A source admitted to being stunned when he read the statement.

“Why did Corzine get involved? Christie savaged him.”

Then he relented.

Cooled off.

He concluded it must be a case of the former governor having a business connection somewhere to the system, the swamp.

Perhaps, he said, unlike others, or one, this former Goldman Sachs governor, at last, belonged.

As bad as Corzine was, he at least surrounded himself with people who knew government and practical politics. Murphy is more inept than Corzine and has surrounded himself with clueless progressive cheerleaders. If the GOP had anyone at all ready to run in 2021, Murphy would be finished, but they have no one.

The story is a crash course in NJ politics. Congrat’s to the reporter.