The Play Under the Play: An Irresistible Confluence of Power Potential

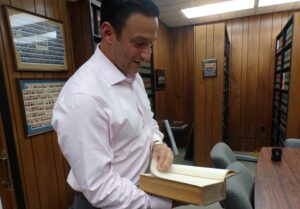

The South Jersey scion of a political family, familiar with the picture of his father and former Governor

Tom Kean, Sr., in the family law office, Mike Testa from the outset looked like a GOP star capable of transcending those predictable parochialisms of the 1st Legislative District. But the confluence of politics and the players involved, including bosses at all levels trying to time 2020 and 2021 – and work the locks of elections like master jewel thieves – for their own triumvirate benefit, could catapult young Testa faster than most thought.

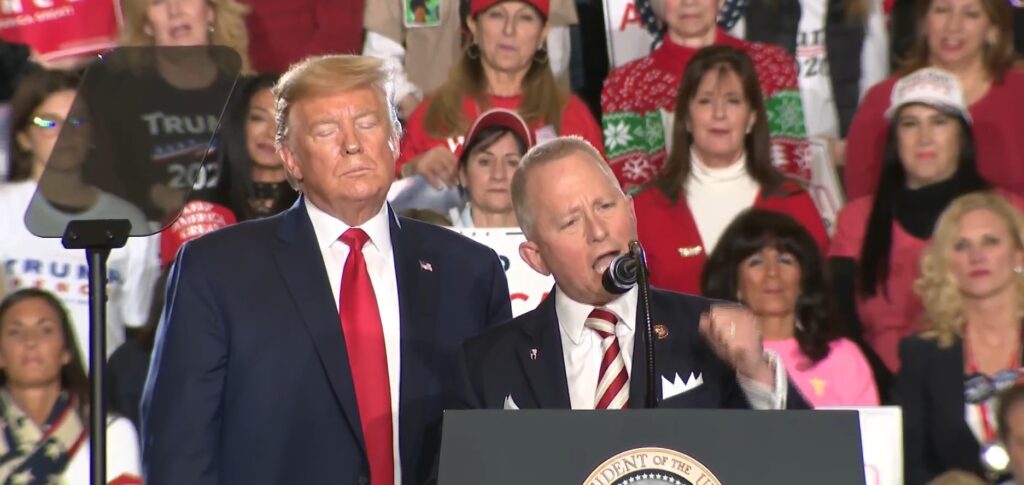

If the overlapping First Legislative and Second Congressional Districts amount to a game of mouse trap, all Testa has to do at this point is stand in place and wait for the seesaw underfoot to flip him upward and forward. Of course, a few things have to happen first, but given the primary players involved – President Donald J. Trump, former Governor Chris Christie, and South Jersey Democratic Leader George Norcross III, and their individual pressing political and business quests – an atmosphere of idleness seems out of the question.

Too many powerful bodies pressed into a small space can only mean one thing, particularly given past history here: politics-playmaking.

The Christie-Norcross connection is obvious.

As a U.S. Attorney who prosecuted numerous Democratic Party leaders, Christie by the end of his tenure

left a few bosses standing, Norcross chief among them, and later as governor counted on that (dominant establishment) wing of the party to drive his agenda. Specifically, he leaned on then state Senator Jeff Van Drew – a Democrat in those days – to supply votes necessary to get his budgets out of committee. Almost anyone on any given day attempting to curry favor with Sweeney could be counted on to supply that (or almost any other Christie-enabling) vote. Such is the nature of senate politics and the power of the senate presidency, but Van Drew especially eagerly supplied what the front office needed. He came from a Republican district and Christie was popular pre-Bridgegate, so pure pragmaticism – and self-preservation – dictated Van Drew’s moves.

The Christie-Norcross partnership – and Van Drew within it as that go-to thumbs-vote in a pinch – functioned well on all fronts. It gave the 1st District Democrat a way to tell his conservative constituents that he backed Republican Christie, spared Senate President Steve Sweeney’s (D-3) from having to return the favor of another Democrat who wouldn’t have wanted to back Christie’s agenda for free, and gave executive Christie what he wanted, and enabled him to brag that he could work with Democrats. In return, of course, Norcross as the prime mover of the South Jersey Legislative Constellation, got what he craved: influence with the governor.

It worked.

That is until Christie cracked up.

By the time he limped out of office with a 16% approval rating, out-blustered by Trump in his presidential bid and never having shaken off the dreadful derailment of the GW Bridge fiasco, Christie had dinner with Norcross in Morristown presumably to talk in part about the future. For Christie, it was time to make money. For Norcross, it was time to continue to make money. The tax incentive plan signed into law by Christie and later exposed and hammered by the Murphy Administration was not dissimilar as a concept from a federal tax incentive plan signed into law by Trump. As a private citizen, Christie would co-found a real estate fund to operate with Hampshire Cos., a Morristown-based investment firm looking to take advantage of the federal tax incentives. They were in a similar business arena now, Norcross and Christie, in addition to politics, with overlapping interests. When the boss needed a legal team to hit back amid headlines about the state tax incentive program, four of Norcross’ six original attorneys on the case stepped forward with strong Christie ties. A year after they dined visibly in Morris County, and amid the tax incentive scandal, Norcross and Christie huddled up at the 21 Club with former Governor Jon Corzine. The partnership appeared robust.

Van Drew would give them another opportunity to reassert their longstanding political alliance.

The decision by the congressman (and former state senator) to change his party affiliation ssooner than back the impeachment of Trump became an opportunity for Norcross and Christie to attempt to put their own fingerprints on a significant symbolic event, or at least exert strategic influence. The timing couldn’t have been better – for all concerned. The ongoing investigation by the state attorney general and the feds into his businesses’ use of the tax incentive program hastened Norcross’ need for strengthened political capital.

He didn’t have the governor anymore. Murphy was too busy not only being liberal – but now also threatening his business and reputation.

But he did have a solid, country club-based friendship with another 1 percenter named Trump, whose political director, Bill Stepien, had cut his teeth as Christie’s political director, including throughout the Bridgegate fiasco.

At the height of his own impeachment, in the almost immediate aftermath of House Speaker Nancy

Pelosi descending on the same Murphy-centric Atlantic City Democratic Convention boycotted by Norcross and Sweeney allies, Trump used Van Drew’s defection to create a New Jersey toehold for a national resurrection narrative. In return, to the extent that anyone cared to draw a line between Van Drew and the South Jersey boss, Norcross presumably could expect certain federal leverage in resisting those persistent Murphy Administration-derived fulminations about his controversial tax incentive partnerships.

Involved through an intimate network of players in the turning of Van Drew and the creation of adhesive appearances that are the basis of politics, Christie too could be owed something, and so too, presumably, could the toiling Trenton workshop of Senate President Sweeney, as a loyal functionary of the Norcross/South Jersey machine, still technically in charge at the state capitol but weakened by a succession of events, not limited to the Democrats’ loss last year of the First District Senate seat.

Van Drew was supposed to have helped hold that seat for Sweeney, but he couldn’t do it, as Testa defeated state Senator Bob Andzeczak (D-1), a result that supposedly infuriated the senate president enough to get him to start openly talking about furnishing a 2020 challenger to Van Drew. Now national-level fundraising heavyweight former U.S. Rep. Patrick Kennedy and his wife, Amy, daughter of a local political heavyweight named Savell, resided in the district. A Democratic Party under siege by rising star Testa – who promptly became co-chair of Trump’s New Jersey campaign – and Van Drew’s subsequent party change – might have warranted macro-micro heavyweight resistance. But the politics of Christie-Norcross and Trump superseded those emotions ultimately best satisfied by blaming Murphy – not Van Drew, at least behind the scenes – for the critical 2019 South Jersey loss of war hero Andrezjczak.

Testa, in fact, had run his campaign, certainly his advertising campaign and the bulk of his messaging even just in casual campaign conversation – by going after Murphy (and to a lesser extent Van Drew, who obviously would get the message); and in this regard, he shared a common enemy of South Jersey Democrats. When he won, a South Jersey Democrat tried to spin his win as a Democratic win: “They can let Mike throw the bombs,” which sounded like an inevitable rationalization by the losing team. But was that all it was? Testa naturally resisted the Democratic governor for ideological reasons, but Sweeney hated him because Murphy had allowed the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) to fund a challenge to his senate seat (the most expensive in U.S. history, with a total $24 million spent, according to the state Election Law Enforcement Commission), and Norcross opposed him in large part for launching the tax incentive inquiry, among other reasons.

Rather than get into the weeds with Testa and endure the torment of Cape May gym rats taunting him about being a Democrat, Van Drew simply changed party affiliation; and Christie – Christie was still Norcross’ kind of guy, in the boss’ own words from back in the Republican’s heyday.

A TV personality with octopus arms to other more exhilarating public interests, Christie looked eager to rebuild something of the crippled empire he had come to depend on men like Norcross to sustain, now alert to political playmaking possibilities, including partial ownership assertion with the most politically pragmatic side of the party-rearranged Van Drew, an old statehouse pal. Then there was Sweeney, another politics chum, growling under the weakening of South Jersey Democrats since the loss of Andrzekczak to Testa and a Russian winter scenario in LD8, where the Dems – with an eye on retaining the LD8 senate seat in 2021 – had failed to dislodge Assemblyman Ryan Peters (R-8).

The Democrats’ war hero Andrzeczak lost, but GOP war hero Peters won.

It was irritating.

And conceivably politically deadly.

For if South Jersey had to endure the loss of Andrzejczak, Peters’ victory meant the possible further

erosion of senate power if the 2019 victorious GOP assemblyman decided to oppose Senator Dawn Addiego (D-8), who had changed parties from Republican to Democrat in her own districtwide (with statewide implications) foreshadowing of Van Drew’s reverse defection a year later.

That was Sweeney – and by extension Norcross, for Peters had defied the boss – and Trump, for that matter, in the name of giving the 8th District independent representation – running out of room.

Christie here had a political play closer to his statewide political origins, with business and political interests still connected to Norcross and Sweeney, and probably ultimately national intentions. The man who now occupied the job Christie once had, Chris Carpenito, had never made full U.S. Attorney. A decided Christie ally but certainly – and who wouldn’t be – lower profile than Christie (and Paul Fishman, who had prosecuted Bridgegate) his ongoing occupancy of the position looked conceivably complicated by the implications of politics in South Jersey. If Trump could use Van Drew to make a case for Democrats losing numbers in blue New Jersey of all places; and Norcross could gain influence with one of his loyal regional subjects toiling very publicly on Trump’s behalf (first in Wildwood, then as an appointee of the Trump Campaign’s fundraising committee); Christie could certainly improve his chances of influencing the choice of the state’s next U.S. Attorney; and – if that candidate’s name was Mike Testa – the next election could give Sweeney (and Norcross) a chance to reclaim dominance in the First Legislative District.

It all fit neatly together, or so it seemed, well packaged among friends, with everyone getting a little something to stay either afloat, relevant, empowered or en vogue.

What was a congressman really, if not a circular way to regain the more advantageous state senate seat and reassert South Jersey’s claim on statewide power, lost amid a tinderbox of events, including Christie’s gubernatorial implosion, Murphy’s un-Corzine-like resistance to Norcross control, a collision for the state party chairmanship lost by Sweeney and Norcross, the aforementioned 2019 midterms, wherein the party’s biggest defeats hurt them while simultaneously helping Murphy, the ongoing tax incentive scandal, and then the acceleration of Murphy’s popularity through the COVID-19 crisis?

And maybe more.

Christie in particular looked energized on the heels of a Supreme Court decision scrapping the

Bridgegate convictions of former cronies Bill Baroni and Bridget Kelly. The case itself had potential precedent-setting implications for Trump himself, combatting his own continuing abuse-of-power alegations.

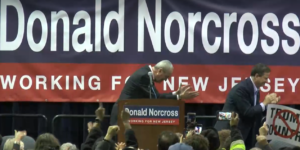

Sweeney and Testa were already all over the governor’s decision-making through the COVID-19 crisis, demanding he reopen the region pronto – if not sooner. The Senate President, moreover, wants a bipartisan investigation of the Murphy Administration’s handling of the COVID crisis. For his part, and maybe almost innocently, Murphy appeared to be signalling a willingness to recognize – at the very least –the NJEA’s fast-shifting stance on Sweeney, while fulfilling his own national politics when he anchor-legged – in full game show host mode – the South Jersey Democratic Party establishment-friendly Pelosi event alongside Norcross brother U.S. Rep. Donald Norcross (D-1).

But it didn’t prevent him from remaining the chief target in the months ahead.

Even if they appear synchronized on that front to a certain degree, the full-throated Testa would also have motivation to move up, if Sweeney – himself an occupant of the Democrats’ 2021 redistricting commission – chose to use the sitting LD1 senator’s home town of Vineland (a Democratic-dominant town) to either strengthen himself in LD3, or attempt to connect Vineland to Atlantic City to create a more Democratic LD1. After weathering the most expensive contest in the legislative history of the United States, Sweeney seemed to have repaired relations with the NJEA sufficiently to avoid a precise repeat of the 2017 fiasco.

Testa’s town has political value, indeed commanded careful scrutiny from the late Alan Rosenthal when the tiebreaking 11th member of the 2011 redistricting commission demanded the creation of more majority-minority districts to free the state legislature from the shackles of too much white male power concentration. If the district remains the way it is, Testa would be in a strong – even unbeatable barring a significant political reengineering – position to regain his seat (unless part of Sweeney’s deal with the NJEA includes redirected resources at Testa). But if the South Jersey Democrats see a way to wrest back the first with the assistance of redistricting (maybe Vineland to LD2, Bridgeton to LD1 to make both more Democratic), Testa could wind up a casualty – or forced into a gladiatorial games posture with fellow Republican state Senator Chris Brown (R-2) – if the reapportionment tiebreaker opts for a Democratic instead of Republican 2021 map.

That strengthens a case for Testa to assume a federal job – and not just any job, but a law enforcement positon that would reanimate the possiton at a time when Murphy’s enemies are still mired in the unresolved tax incentive scandal. Given his high visibility early, willingness to take on statewide causes, and political ambition, a deputy installation in D.C. seems unlikely, especially with the opportunity proximity of Christie in South Jersey whose longstanding political ties to Norcross, and the Trump-Van Drew totem.

U.S. Attorney looked like a play, at the very least.

Ultimately maybe the Trump connection would be enough for those Jersey-based powers to make protecting Testa districtwide in 2021 a strong enough move to remain in the president’s good graces, but for the U.S. Attorney scenario to work, all Testa would have to do at this point in this specific regard is wait for the politics to play out around him, while continuing to repeatedly aggressively hit Governor Murphy – the favorite mutual target of Sweeney, Norcross and Christie – in politics that makes sense for his district, as it does for the congressional district of fellow Republican Van Drew, while in the immediate campaign co-chair service of an Election Year-focused Trump.

With the current continued implosions by Trump, it is unlikely that a Republican will serve as US Attorney for long after January 2021.